In this course, learn how to create a Portable Hand Tool Case using a combination of power tools and hand tools. Over 3 hours of detailed video instruction describe how to create the hand tool case. Includes a short course in creating dovetails. The tool case has integrated stands to keep the two halves up while working at a workbench. Tips + techniques are provided for creating + fitting drawers, using hand tools + machines, creating dovetails. Detailed, printable CAD diagrams included. Follow along and build your own Hand Tool Case. You are guided through the build process from a board to the final Hand Tool Case. I share techniques and processes to create and precisely fit drawers in their compartments and how to locate + install the tool dividers.

Watch the process of how I lay out a series of hand tools to determine the best layout for the dividers in the hand tool case. Discover how to create dovetail joinery to use in your next projects. The build, plans and course are based on skills developed in a functioning furniture making studio. My build techniques, processes, tips and techniques will benefit you in your future projects.

Includes detailed, printable CAD drawings with measurements

Over 3 hours of video instruction in 12 modules and 13 videos

Includes

-

Detailed, colored, printable CAD diagrams of all components with precise measurements

-

Over 3 hours of detailed, comprehensive video instruction. Follow the plan and diagrams to build your own Portable Hand Tool Case

-

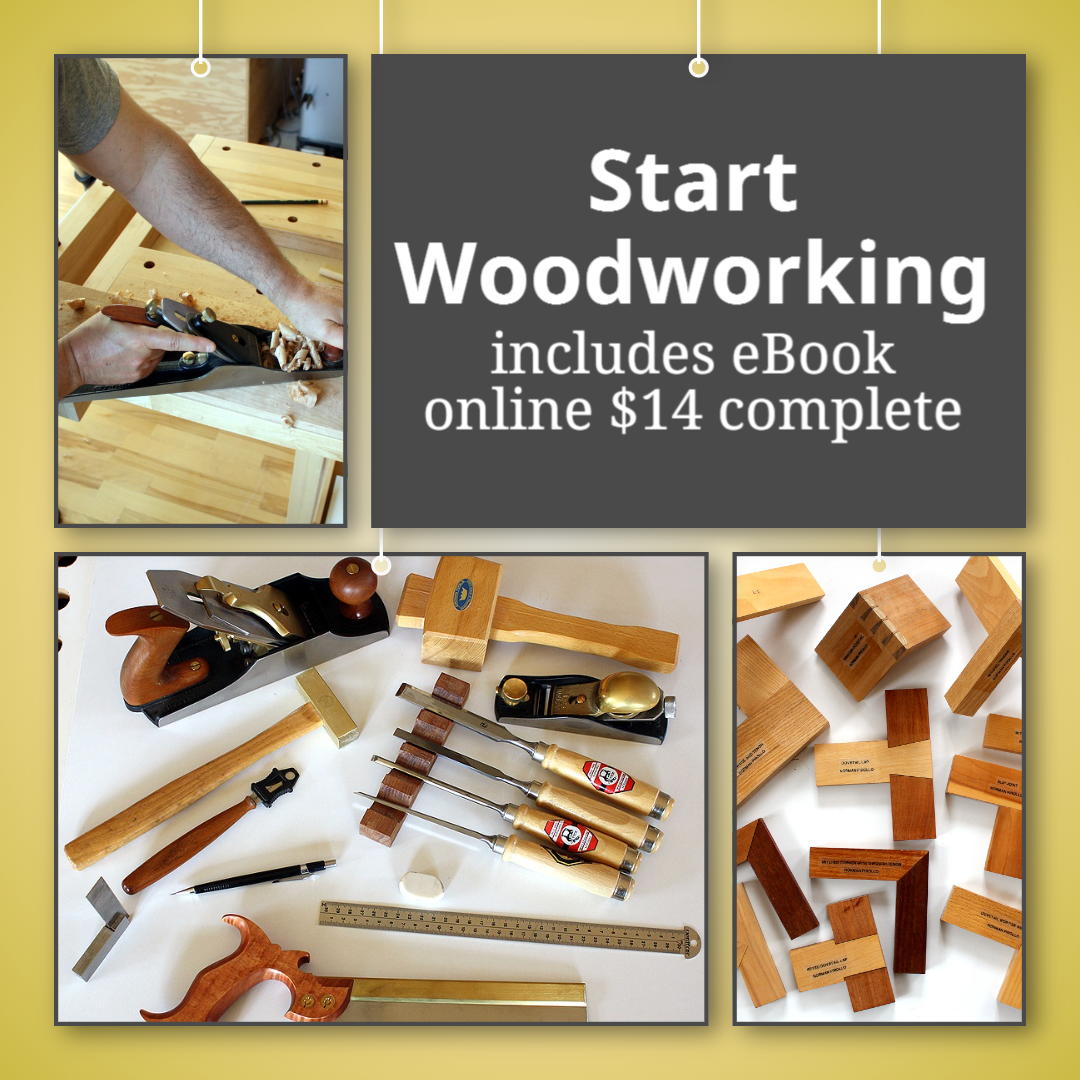

Includes Start Woodworking (eBook)

What you will learn

-

How to layout and dimension wood

-

Design concepts of a Portable Hand Tool Case

-

How to design a Hand Tool Case for your own tools

-

How to create strong, precise dovetail joinery

-

How to precisely fit parts together in a project

-

How to effectively use small hand planes in your furniture projects

-

Learn a trouble-free method to assemble a case

-

Learn how to create a rabbet joint for drawers and back panels

-

Learn techniques to accurately line up components in a project

-

How to use a shooting board

-

How to use a bench hook

-

How to make drawers in exact dimensions

-

Learn techniques to piston fit drawers in their compartment

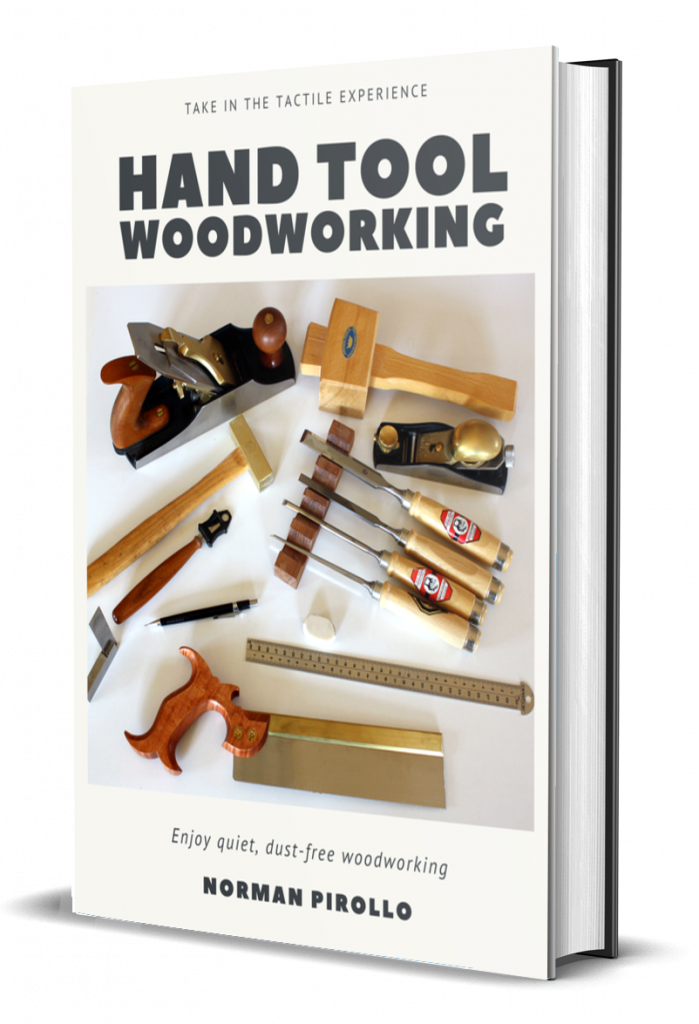

START WOODWORKING (eBook, 115 pgs., $15) included with this course

Purchase Hand Tool Case with (3+ hrs. of videos) and plans for $40

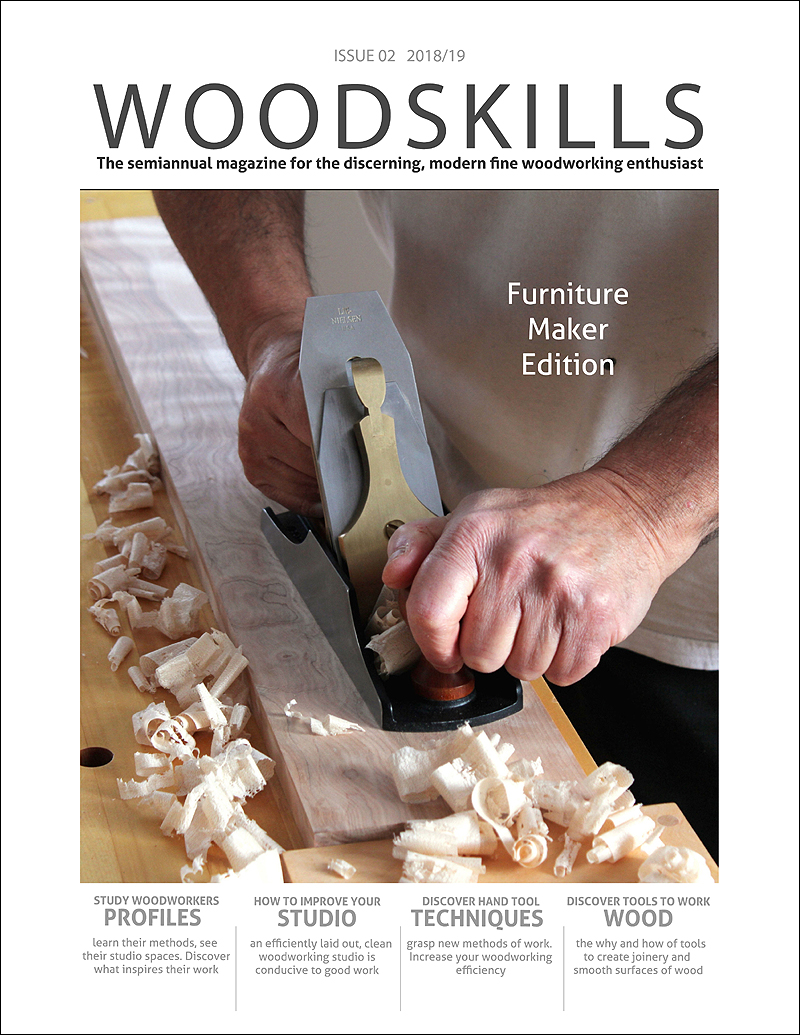

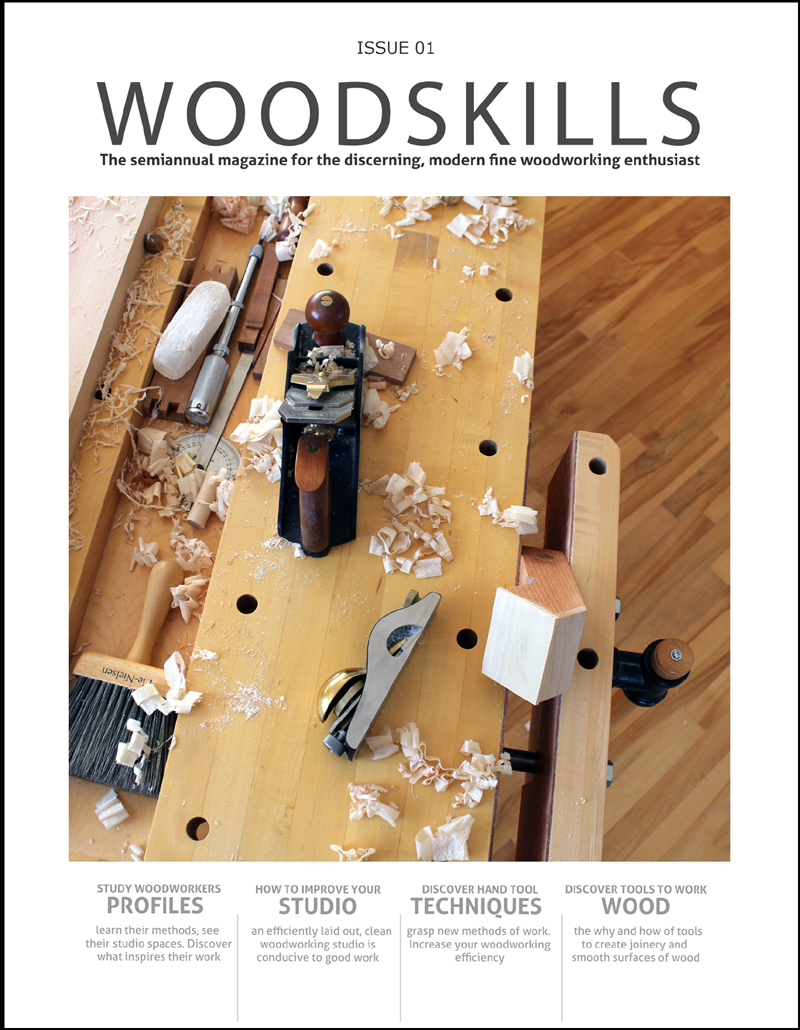

Norman maintains a blog of ongoing projects in his studio: Pirollo Design Blog as well as having written and published over six books in recent years. Books, magazines where authors furniture, work methods and philosophy have been featured:

Quiet Woodworking (New Art Press)

Hand Tool Woodworking (New Art Press)

Start Woodworking (New Art Press)

Craftisian Interview (Norman Pirollo)

HackSpace Magazine – Make With Wood April 2020

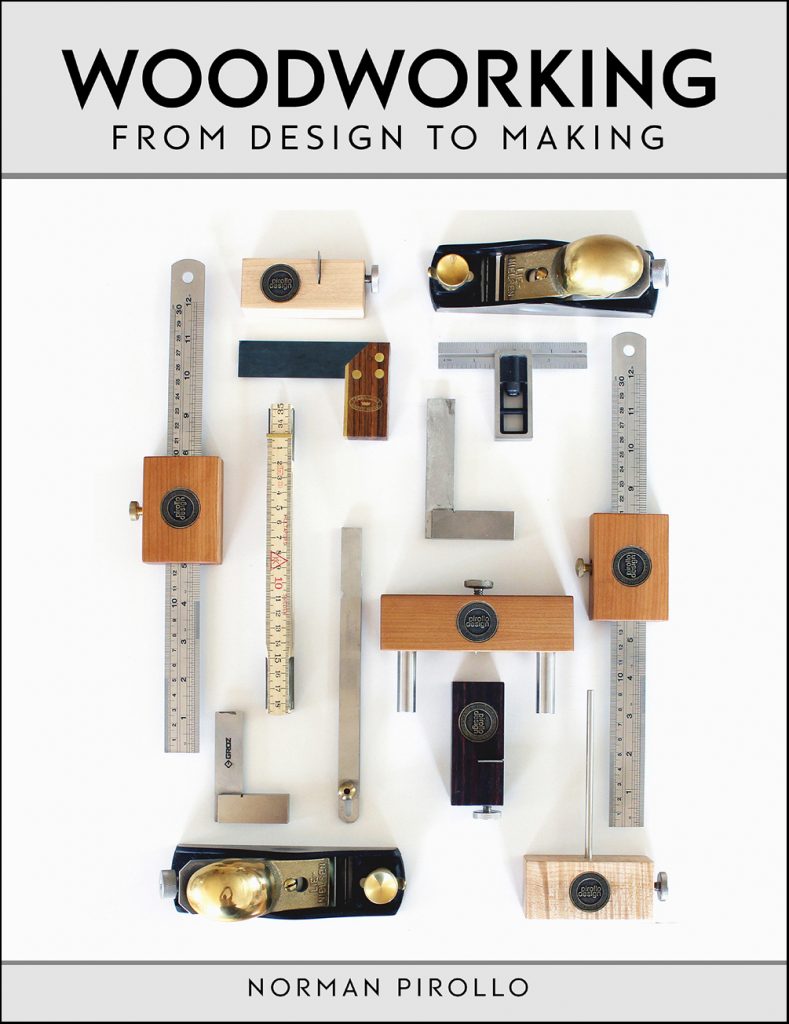

Woodworking: From Design To Making (New Art Press)

The Wood Artist: Creating Art Through Wood (New Art Press)

From Hi-Tech to Lo-Tech: A Woodworker’s Journey (NAP)

Start Your Own Woodworking Business (New Art Press)

Rooted: Contemporary Studio Furniture (Schiffer Publishing)

IDS15 (Studio North)

IDS14 (Studio North)

Canadian Woodworking magazine Jan. 2015

Our Homes magazine Fall 2014

IDS14 (Studio North)

NICHE Magazine Winter 2013

Fine Woodworking Magazine – 4 Bench Jigs for Handplanes

Fine Woodworking Magazine – Essential Shopmade Jigs

Woodwork magazine

Wood Art Today 2 (Schiffer Books)

500 Cabinets ( Lark Books)

Studio Furniture: Today’s Leading Woodworkers (Schiffer)

Canadian Interiors Design Source Guide

Ottawa Life magazine (Profile,work) 2012

Panoram Italia magazine

Our Homes magazine

Craft Journal

Display cabinet on custom splayed leg stand to introduce stability in a compact form. Designed to display art and decorative pieces. Tambour styled doors. Interior of asymmetrically arranged dovetailed drawers. Tambours are composed of Pau Amarello; a deep yellow colored wood to contrast with light maple cabinet. Drawer fronts of Black cherry. A timeless design of a cabinet on uniquely arranged stand using natural, domestic woods. Individual hinged doors provide access to either side of the cabinet drawers and compartments. Display cabinet introduces a subtle, contemporary aesthetic. Natural shellac finish provides protection yet maintains a tactile wood surface.

Display cabinet on custom splayed leg stand to introduce stability in a compact form. Designed to display art and decorative pieces. Tambour styled doors. Interior of asymmetrically arranged dovetailed drawers. Tambours are composed of Pau Amarello; a deep yellow colored wood to contrast with light maple cabinet. Drawer fronts of Black cherry. A timeless design of a cabinet on uniquely arranged stand using natural, domestic woods. Individual hinged doors provide access to either side of the cabinet drawers and compartments. Display cabinet introduces a subtle, contemporary aesthetic. Natural shellac finish provides protection yet maintains a tactile wood surface.

Also interesting are the dovetailed drawer fronts. I was striving for a wood tone not as dark as cherry and not light, just sufficient to provide some contrast to the maple. The wood originates from leftover European Beech offcuts used in a cabinet made in 2008 that was featured in the forward of the “500 Cabinets” book.

Also interesting are the dovetailed drawer fronts. I was striving for a wood tone not as dark as cherry and not light, just sufficient to provide some contrast to the maple. The wood originates from leftover European Beech offcuts used in a cabinet made in 2008 that was featured in the forward of the “500 Cabinets” book.

Norman Pirollo, successful founder of White Mountain Design, White Mountain Toolworks, Refined Edge Design, WoodSkills and Pirollo Design, guides you through the process of starting and setting up your own woodworking business. Learn from an experienced business person in this field. Norman provides the necessary expertise and answers questions about starting your own woodworking business in this information packed course.

Norman Pirollo, successful founder of White Mountain Design, White Mountain Toolworks, Refined Edge Design, WoodSkills and Pirollo Design, guides you through the process of starting and setting up your own woodworking business. Learn from an experienced business person in this field. Norman provides the necessary expertise and answers questions about starting your own woodworking business in this information packed course.

Maple display cabinet with book-matched spalted maple veneered doors, Black Limba drawers and stand. Spalted maple drawer pulls. Solid brass knife hinges. The cabinet has a large component of hand work and fitting involved. The interior is partitioned into three drawers and a shelf to hold art objects, sculptures or objects of value. The doors have been book-matched in the form of interesting flame graphics to accentuate the unique grain pattern of the spalted maple wood used. Surfaces are hand scraped and formed. The drawers are assembled using dovetail joinery. Meticulous attention provided to detail and finishing. The wood is its natural color. The cabinet is finished with multiple coats of thinned shellac, polished and waxed.

Maple display cabinet with book-matched spalted maple veneered doors, Black Limba drawers and stand. Spalted maple drawer pulls. Solid brass knife hinges. The cabinet has a large component of hand work and fitting involved. The interior is partitioned into three drawers and a shelf to hold art objects, sculptures or objects of value. The doors have been book-matched in the form of interesting flame graphics to accentuate the unique grain pattern of the spalted maple wood used. Surfaces are hand scraped and formed. The drawers are assembled using dovetail joinery. Meticulous attention provided to detail and finishing. The wood is its natural color. The cabinet is finished with multiple coats of thinned shellac, polished and waxed.

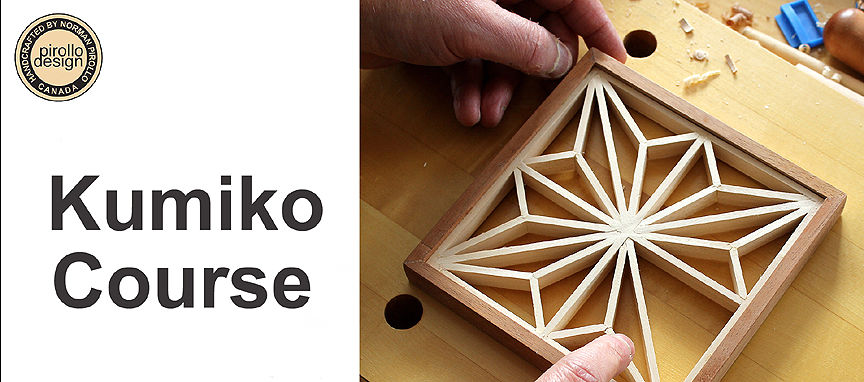

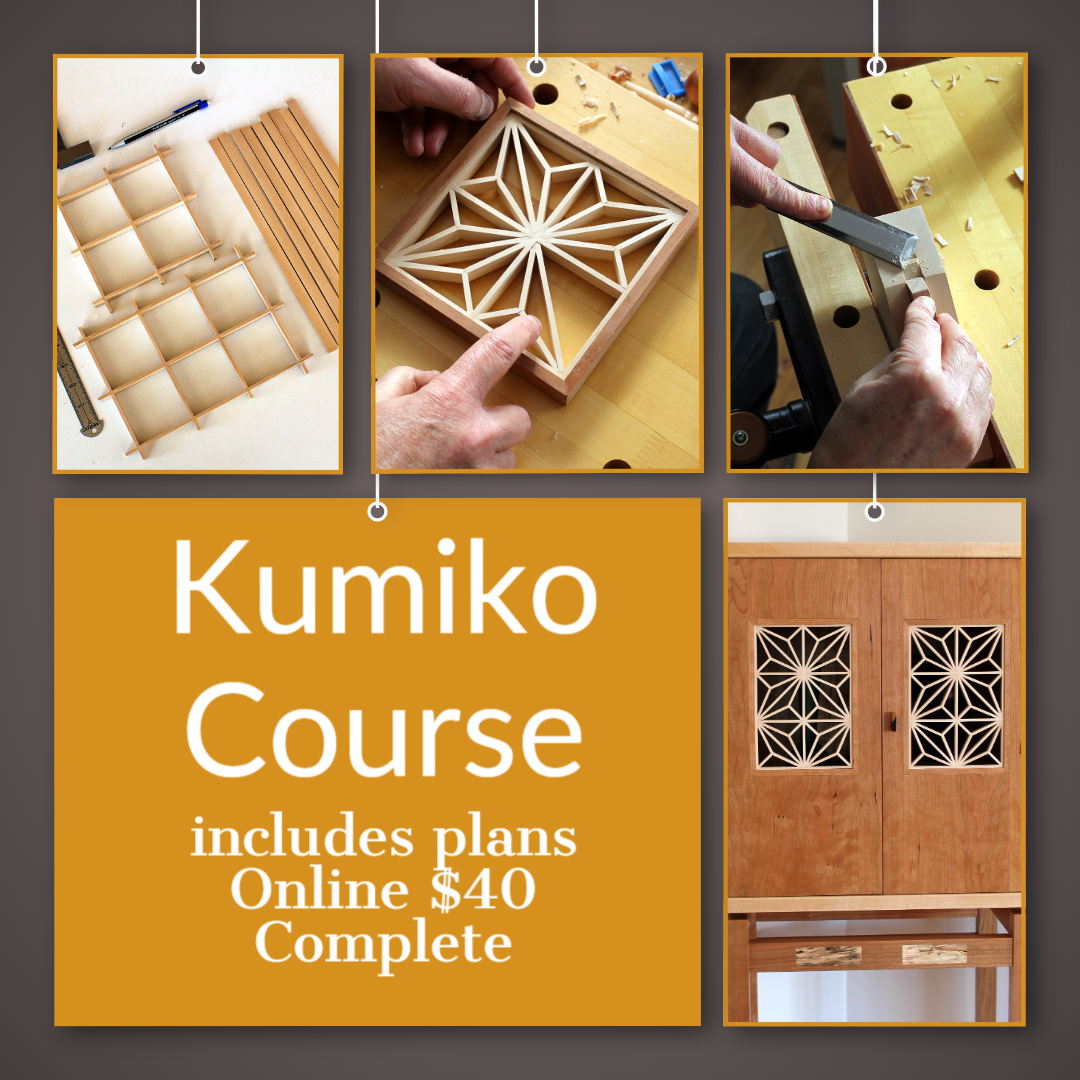

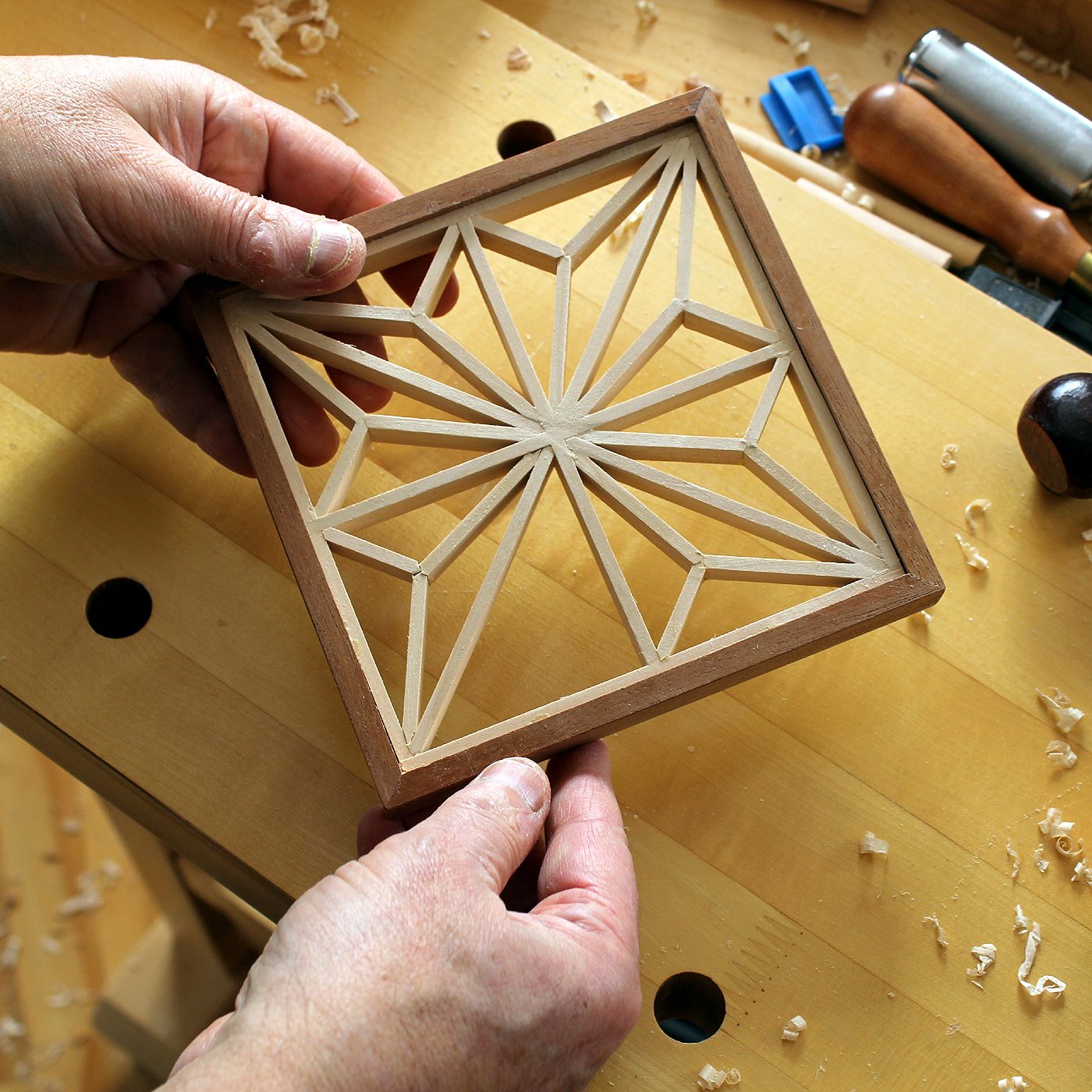

Kumiko display cabinet with solid cherry doors and Kumiko inserts, cherry drawers, and two-tone cocobolo door and drawer pulls. Exterior of the cabinet is composed of hand cut maple veneers whereas the interior is composed of hand cut soft maple veneers. Solid brass knife hinges used. The cabinet has a large component of hand work and fitting involved. The contrasting cabinet stand is made with hand selected black cherry with contrasting inlay. The interior is partitioned into two halves that are individually accessible when either door is open. The doors have embedded Kumiko panels to transfer light from within cabinet and to see art objects from outside. Surfaces are hand scraped and formed. Drawers are assembled using dovetail joinery. Meticulous attention provided to detail and finishing. The wood is its natural color. Cabinet is finished with multiple coats of thinned shellac, polished and waxed.

Kumiko display cabinet with solid cherry doors and Kumiko inserts, cherry drawers, and two-tone cocobolo door and drawer pulls. Exterior of the cabinet is composed of hand cut maple veneers whereas the interior is composed of hand cut soft maple veneers. Solid brass knife hinges used. The cabinet has a large component of hand work and fitting involved. The contrasting cabinet stand is made with hand selected black cherry with contrasting inlay. The interior is partitioned into two halves that are individually accessible when either door is open. The doors have embedded Kumiko panels to transfer light from within cabinet and to see art objects from outside. Surfaces are hand scraped and formed. Drawers are assembled using dovetail joinery. Meticulous attention provided to detail and finishing. The wood is its natural color. Cabinet is finished with multiple coats of thinned shellac, polished and waxed.

Solid beech display cabinet with figured wood drawer fronts and blackwood pulls on doors and drawers. Solid brass knife hinges. The cabinet has a large component of hand work and fitting involved. The interior is partitioned into two drawers and a shelf to hold art objects, sculptures or objects of value. The beech doors are uniform in appearance adding to a clean, contemporary aesthetic. Surfaces are hand scraped and formed. The drawers are assembled using dovetail joinery. Meticulous attention provided to detail and finishing. The wood is its natural color. Cabinet is finished with multiple coats of thinned shellac, polished and waxed.

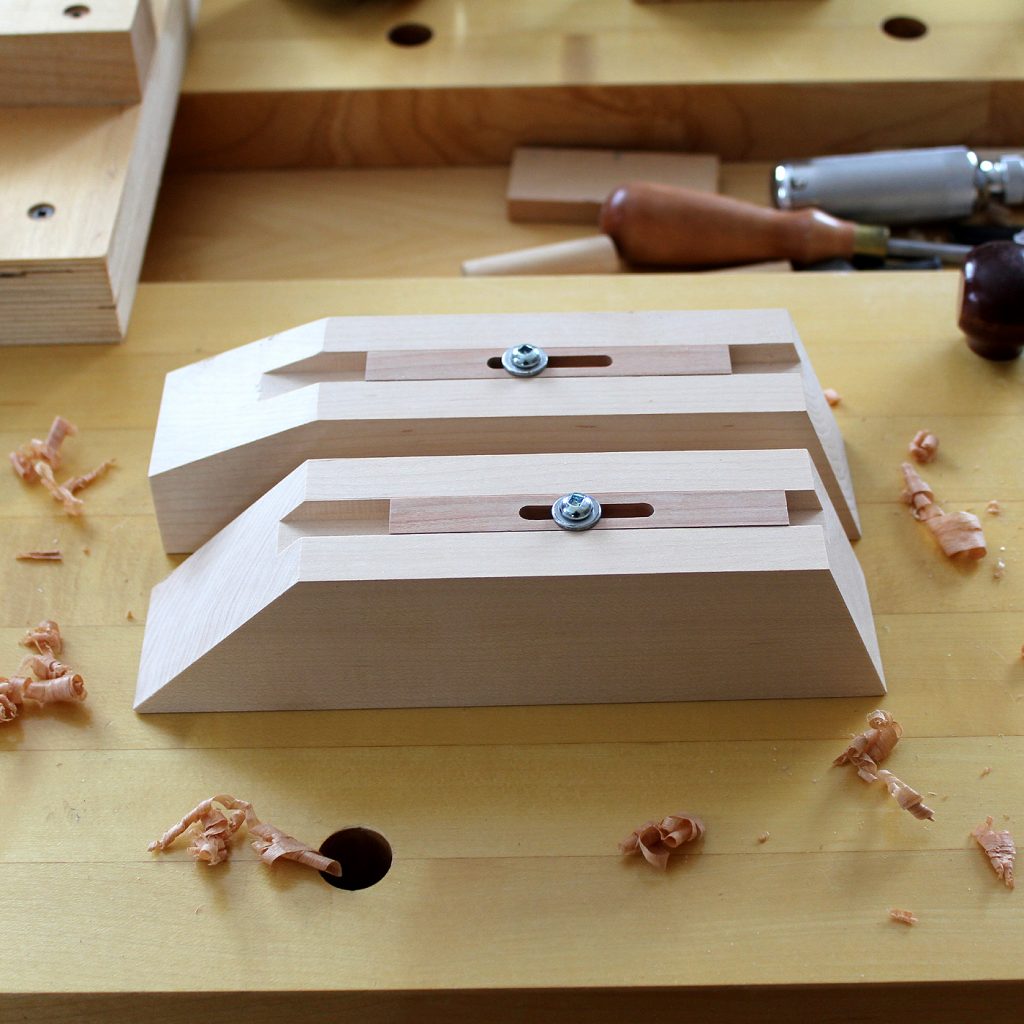

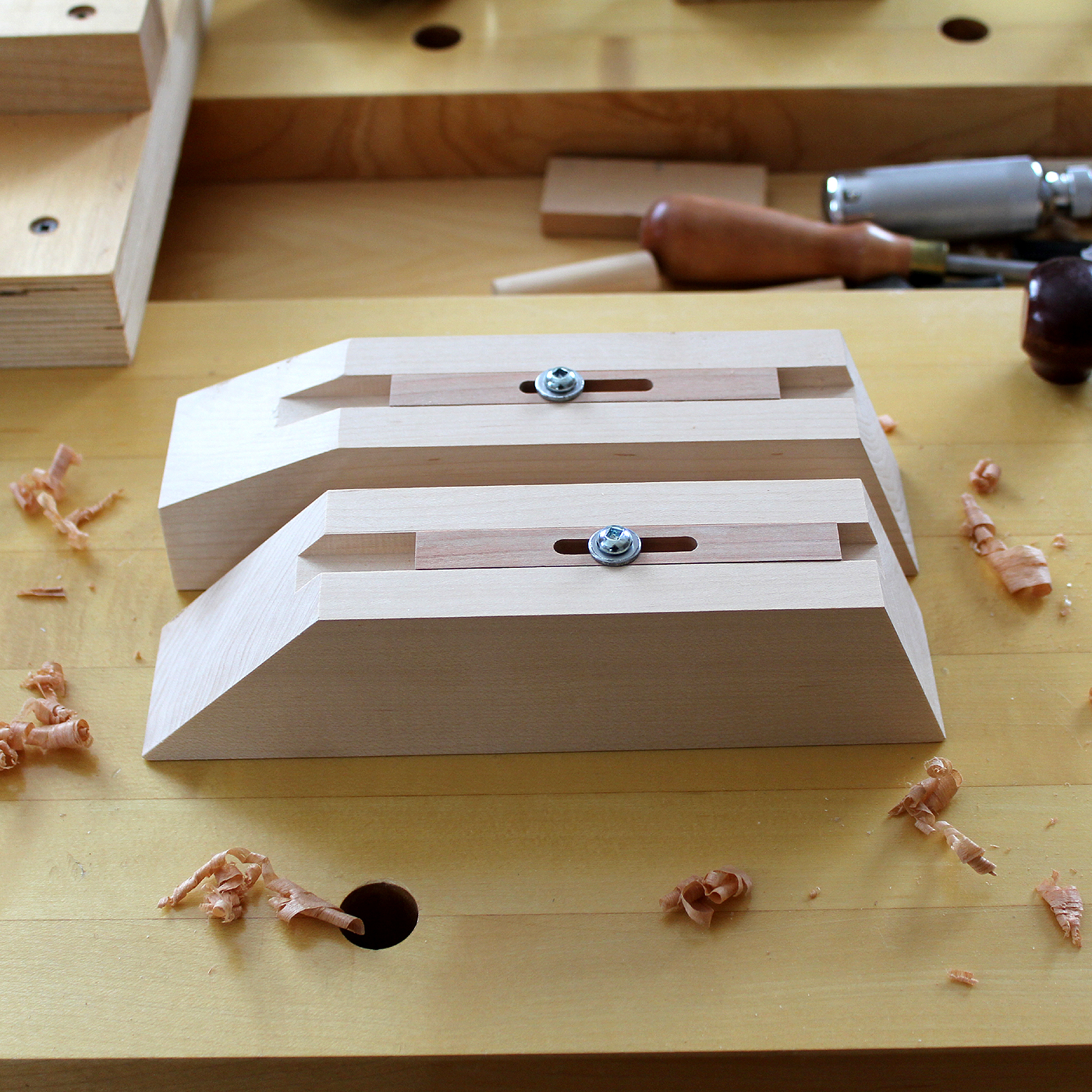

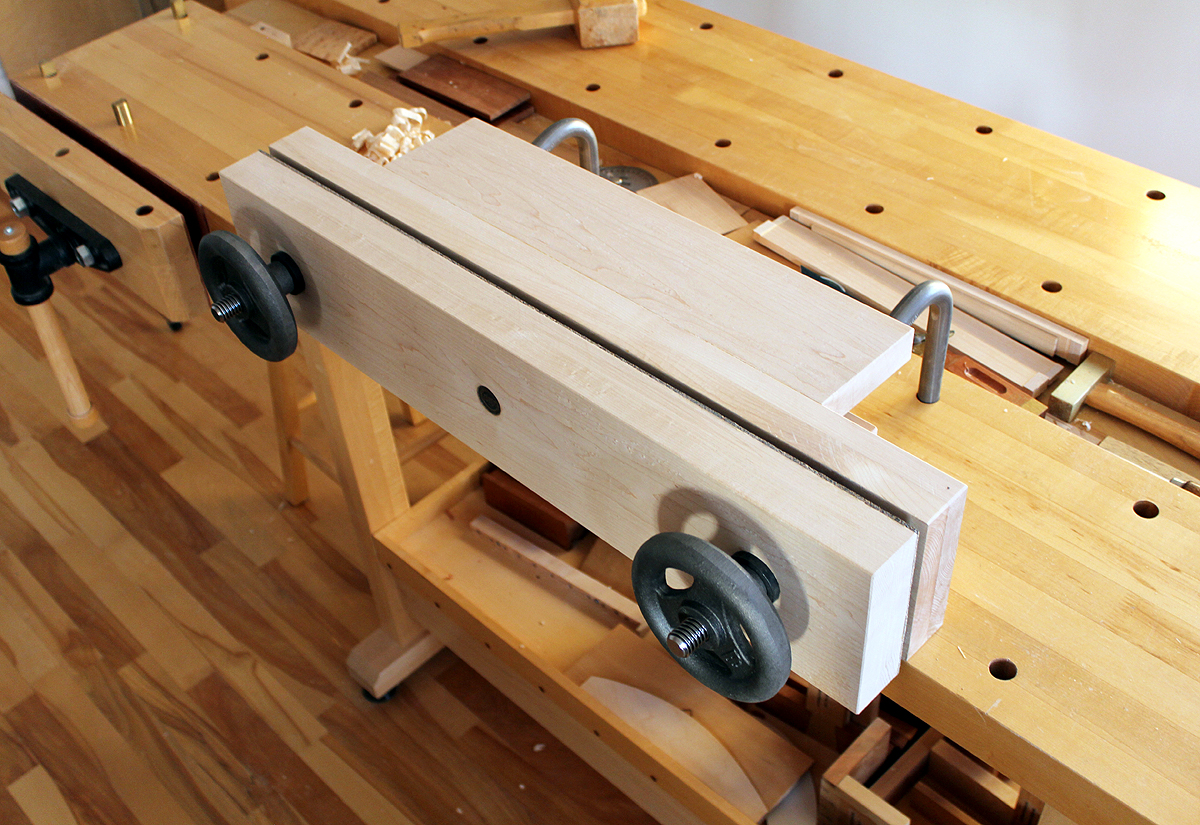

Solid beech display cabinet with figured wood drawer fronts and blackwood pulls on doors and drawers. Solid brass knife hinges. The cabinet has a large component of hand work and fitting involved. The interior is partitioned into two drawers and a shelf to hold art objects, sculptures or objects of value. The beech doors are uniform in appearance adding to a clean, contemporary aesthetic. Surfaces are hand scraped and formed. The drawers are assembled using dovetail joinery. Meticulous attention provided to detail and finishing. The wood is its natural color. Cabinet is finished with multiple coats of thinned shellac, polished and waxed. Narrow version of sliding tail vise seen in the image above and below. Works with a single bench dog hole in end vise. Locks workpiece firmly in place to allow handplaning along the grain or creating profiles along edge of boards. Can be easily removed and installed. Bolt is optionally tightened for larger workpieces.

Narrow version of sliding tail vise seen in the image above and below. Works with a single bench dog hole in end vise. Locks workpiece firmly in place to allow handplaning along the grain or creating profiles along edge of boards. Can be easily removed and installed. Bolt is optionally tightened for larger workpieces.

Norman maintains a blog of ongoing projects in his studio at:

Norman maintains a blog of ongoing projects in his studio at:

A spin off of the maker movement has been the return to creating one’s own furniture. In fact, a large and growing segment of the maker movement revolves around designing and building furniture. The best part of this is how young people have once again embraced the creation of their own furniture for reasons different than in the past. In the past, the younger consumer could not afford furniture so instead built their own. Today, the reasons for building your own furniture revolve around handcrafting, channelling creativity into a furniture design, and the process of creating an object. It isn’t so much about the result but the experience of getting there. Younger makers today are turning furniture design on its ear by shunning age old design constructs and paradigms, and instead embracing a fresh outlook on furniture design.

A spin off of the maker movement has been the return to creating one’s own furniture. In fact, a large and growing segment of the maker movement revolves around designing and building furniture. The best part of this is how young people have once again embraced the creation of their own furniture for reasons different than in the past. In the past, the younger consumer could not afford furniture so instead built their own. Today, the reasons for building your own furniture revolve around handcrafting, channelling creativity into a furniture design, and the process of creating an object. It isn’t so much about the result but the experience of getting there. Younger makers today are turning furniture design on its ear by shunning age old design constructs and paradigms, and instead embracing a fresh outlook on furniture design. In the past, bolder and radical furniture designs were the product of reclusive studio furniture makers with limited means of communicating with one another. Today instead, younger makers are informed primarily through social media. Practicality and functionality of design have become the new criteria for furniture design. The furniture of this new generation of makers embraces universality and democratizes design. Social media plays an important part in design today within the maker movement. Through social media, furniture designs have become instantly available to both inform and influence other makers. Through social media, makers can quickly adapt an existing design to their own aesthetic or style. The process of fleshing out designs is considerably accelerated through social media and democratization.

In the past, bolder and radical furniture designs were the product of reclusive studio furniture makers with limited means of communicating with one another. Today instead, younger makers are informed primarily through social media. Practicality and functionality of design have become the new criteria for furniture design. The furniture of this new generation of makers embraces universality and democratizes design. Social media plays an important part in design today within the maker movement. Through social media, furniture designs have become instantly available to both inform and influence other makers. Through social media, makers can quickly adapt an existing design to their own aesthetic or style. The process of fleshing out designs is considerably accelerated through social media and democratization. So from what I observe, things are looking up for furniture making and woodworking in general. There is a resurgence occurring in this decades old creative outlet. A new awareness of the virtues and benefits of creating objects using wood as a medium is occurring. I am fairly active on social media and an often awed by radical new furniture designs from this new maker movement. Along with this, the democratization of design will hopefully benefit us all as we can extract elements of shared designs to incorporate into our own work.

So from what I observe, things are looking up for furniture making and woodworking in general. There is a resurgence occurring in this decades old creative outlet. A new awareness of the virtues and benefits of creating objects using wood as a medium is occurring. I am fairly active on social media and an often awed by radical new furniture designs from this new maker movement. Along with this, the democratization of design will hopefully benefit us all as we can extract elements of shared designs to incorporate into our own work.

My first attempt was to use some highly figured veneer I had stored away. It is commercial veneer so very thin. The veneer itself is beautiful, light in color and would make the interior of the beech cabinet pop. First step was to scrape down the surface of the drawer fronts and glued a piece of this veneer to each. Did this successfully and began to create the mortises for the new pulls. However, there is something about commercial veneer that doesn’t sit well with me and I was not able to get past this. The thickness of the material is paper (thick paper) thin and brittle, too fragile for my taste.

My first attempt was to use some highly figured veneer I had stored away. It is commercial veneer so very thin. The veneer itself is beautiful, light in color and would make the interior of the beech cabinet pop. First step was to scrape down the surface of the drawer fronts and glued a piece of this veneer to each. Did this successfully and began to create the mortises for the new pulls. However, there is something about commercial veneer that doesn’t sit well with me and I was not able to get past this. The thickness of the material is paper (thick paper) thin and brittle, too fragile for my taste. After some judicious mortising using chisels and a mallet,, then some paring, the drawer pull mortises were created as seen above. The most critical part of this step is to remove the top-most layer of wood; it is so easy to tearout the surrounding wood if the chisel cuts are not clean. Then it is simply a matter of cutting and paring to the correct depth of the tenon for the drawer pull. Contemporary-styled blackwood pull temporarily inserted below.

After some judicious mortising using chisels and a mallet,, then some paring, the drawer pull mortises were created as seen above. The most critical part of this step is to remove the top-most layer of wood; it is so easy to tearout the surrounding wood if the chisel cuts are not clean. Then it is simply a matter of cutting and paring to the correct depth of the tenon for the drawer pull. Contemporary-styled blackwood pull temporarily inserted below. So very happy with the outcome and will be completely replacing the doors of the cabinet next. I intend to use veneered figured wood for the doors, similar wood (Ambrosia Maple) as the drawer fronts. I plan to write a detailed article about this in the next issue of

So very happy with the outcome and will be completely replacing the doors of the cabinet next. I intend to use veneered figured wood for the doors, similar wood (Ambrosia Maple) as the drawer fronts. I plan to write a detailed article about this in the next issue of

Available here:

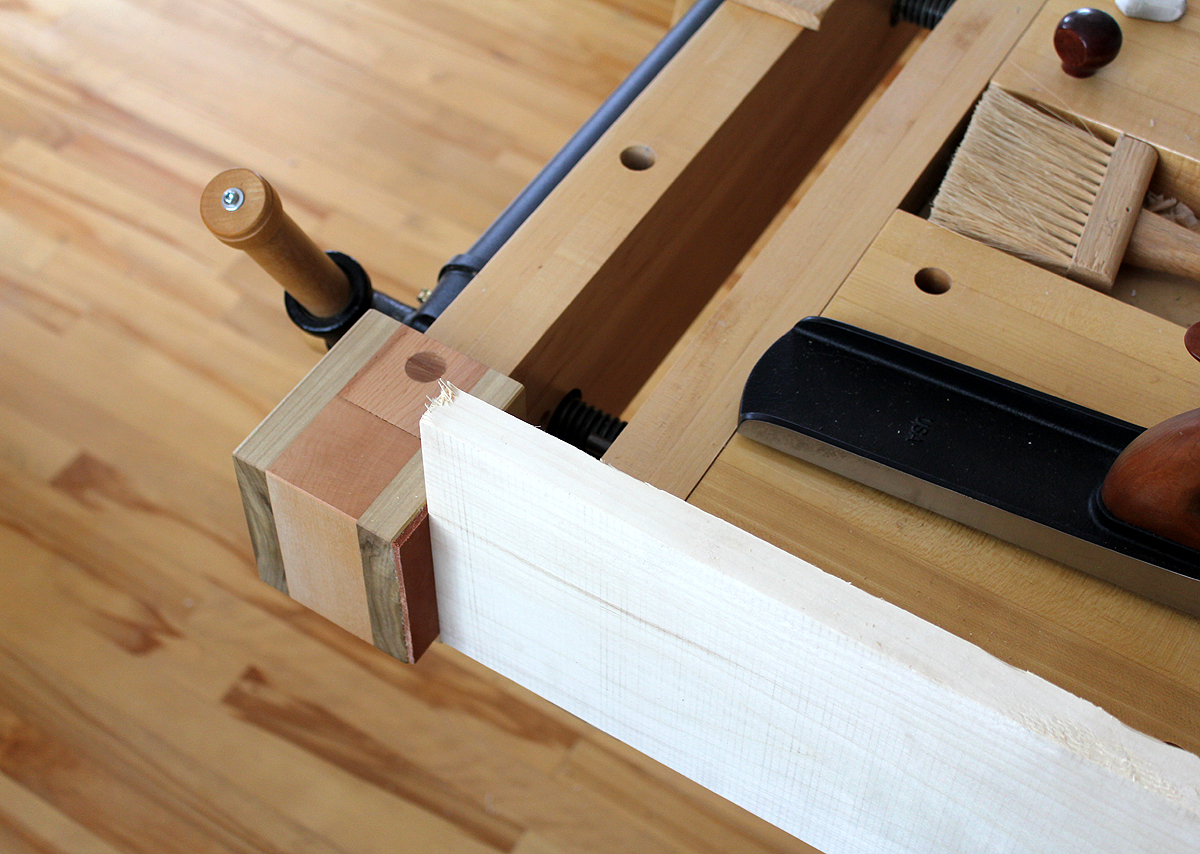

Available here:  A good example of how an edge dog can be used to hold a board on edge can be seen in the following image. One end is held by a edge dog whereas the other end is an add-on to a twin-screw vise which I discuss next. Instead of clamping a board to the surface of a workbench, the edge dog is used to clamp the board along the workbench edge and therefore at a more reasonable and lower height suitable for handplaning. Having a pair of these edge dogs allows either side of the workbench to be used. The edge dogs are created with opposing configurations as shown above.

A good example of how an edge dog can be used to hold a board on edge can be seen in the following image. One end is held by a edge dog whereas the other end is an add-on to a twin-screw vise which I discuss next. Instead of clamping a board to the surface of a workbench, the edge dog is used to clamp the board along the workbench edge and therefore at a more reasonable and lower height suitable for handplaning. Having a pair of these edge dogs allows either side of the workbench to be used. The edge dogs are created with opposing configurations as shown above. My current workbenches do not incorporate dedicated tail vises. In place, I use a Veritas Twin-screw vise which performs as a tail vise when clamping boards on their face. When it comes to clamping boards on edge, the twin-screw vise can also be used along with bench dogs. The edge of the workpiece would be then sitting on the workbench top. However, this raises the height of the board considerably and is not very conducive to handplaning or jointing an edge of a board. Ideally, the edge of a board should be slightly higher than the workbench surface to effectively perform handplane operations. With this in mind, I created this outboard add-on to the twin-screw vise which extends the width of the vise movable jaw past the edge of the workbench.

My current workbenches do not incorporate dedicated tail vises. In place, I use a Veritas Twin-screw vise which performs as a tail vise when clamping boards on their face. When it comes to clamping boards on edge, the twin-screw vise can also be used along with bench dogs. The edge of the workpiece would be then sitting on the workbench top. However, this raises the height of the board considerably and is not very conducive to handplaning or jointing an edge of a board. Ideally, the edge of a board should be slightly higher than the workbench surface to effectively perform handplane operations. With this in mind, I created this outboard add-on to the twin-screw vise which extends the width of the vise movable jaw past the edge of the workbench. Shown above, this newly designed outboard add-on accessory is an addition to the twin-screw movable jaw. In effect, the vise now becomes an enhanced tail vise capable of clamping boards on edge along the side of a workbench. The clamping is done in conjunction with the previously mentioned edge dog. Images of a board being clamped between these two accessories are shown below.

Shown above, this newly designed outboard add-on accessory is an addition to the twin-screw movable jaw. In effect, the vise now becomes an enhanced tail vise capable of clamping boards on edge along the side of a workbench. The clamping is done in conjunction with the previously mentioned edge dog. Images of a board being clamped between these two accessories are shown below. In these photos I am jointing the edge of a white ash board. I was surprised at how tightly the board is clamped with minimal tension applied to the twin screw vise. The friction from the leather pads contribute to this as slightly more tension was necessary before applying the leather pads. The outboard extension to the twin-screw vise is removable and can be adapted to either side of the twin-screw vise. I am left-handed so having it located to the right of the vise as shown, is more practical. For right-handed use, the opposite edge of the workbench would be used for jointing. As an added bonus, there is no racking of the twin-screw vise regardless of the clamping pressure I apply to the outboard extension.

In these photos I am jointing the edge of a white ash board. I was surprised at how tightly the board is clamped with minimal tension applied to the twin screw vise. The friction from the leather pads contribute to this as slightly more tension was necessary before applying the leather pads. The outboard extension to the twin-screw vise is removable and can be adapted to either side of the twin-screw vise. I am left-handed so having it located to the right of the vise as shown, is more practical. For right-handed use, the opposite edge of the workbench would be used for jointing. As an added bonus, there is no racking of the twin-screw vise regardless of the clamping pressure I apply to the outboard extension.

After a period of testing, I was pleasantly surprised at how well it works. It is completely unobtrusive and designed to accept standard 3/4 inch or 20 mm accessories such as surface clamps, bench dogs and shop-made planing stops. The portable board jack can be adapted to any slab-type workbench top without an existing apron or skirt as can be seen in the images. A face vise at one end keeps the board securely clamped on edge. Jointing the edge of long boards has become so much easier and second nature to me now.

After a period of testing, I was pleasantly surprised at how well it works. It is completely unobtrusive and designed to accept standard 3/4 inch or 20 mm accessories such as surface clamps, bench dogs and shop-made planing stops. The portable board jack can be adapted to any slab-type workbench top without an existing apron or skirt as can be seen in the images. A face vise at one end keeps the board securely clamped on edge. Jointing the edge of long boards has become so much easier and second nature to me now. The hole arrangement on the portable board jack is optimized for the work I do but can be modified if necessary. I no longer give any thought to attaching or clamping a long board on edge and along its length to my workbenches. Often, I simply need a peg to be able to rest the free end of a board on. This allows me to quickly and easily flip the board around to work both long edges.

The hole arrangement on the portable board jack is optimized for the work I do but can be modified if necessary. I no longer give any thought to attaching or clamping a long board on edge and along its length to my workbenches. Often, I simply need a peg to be able to rest the free end of a board on. This allows me to quickly and easily flip the board around to work both long edges. Now, I just selected my most-often used side of a workbench to work on and leave the portable board jack attached. In the future, I will possibly be creating another board jack for my other, similar workbench. This adds to the versatility since it will no longer be necessary to move the board jack from bench to bench.

Now, I just selected my most-often used side of a workbench to work on and leave the portable board jack attached. In the future, I will possibly be creating another board jack for my other, similar workbench. This adds to the versatility since it will no longer be necessary to move the board jack from bench to bench. Next up in the forthcoming installment or Part 2, a couple of cool bench accessories that continue with the theme of attaching and clamping long boards to a workbench. These are boards that are too long to simply clamp to a face vise. It just makes it so much more pleasant to perform handplaning or hand tool tasks once a board or panel is securely clamped. I like for this to be straightforward so I can focus on the task I need to perform instead of spending needless time on securely attaching and clamping a board to a workbench.

Next up in the forthcoming installment or Part 2, a couple of cool bench accessories that continue with the theme of attaching and clamping long boards to a workbench. These are boards that are too long to simply clamp to a face vise. It just makes it so much more pleasant to perform handplaning or hand tool tasks once a board or panel is securely clamped. I like for this to be straightforward so I can focus on the task I need to perform instead of spending needless time on securely attaching and clamping a board to a workbench. Follow our Moxon vise plan and build your own portable Moxon twin-screw vise. The portable Moxon vise is designed to hold work above the standard height of a workbench. The Moxon vise design is widely attributed to a Joseph Moxon. Joseph Moxon (1627 – 1691), was the hydrographer to Charles II English printer specialising in mathematical books and maps. Moxon’s 17th century book The Art of Joinery first described the double-screw vise. In this historical publication the Moxon vise was documented – a double-screw held to a workbench top with clamps or holdfasts in order to facilitate certain work.

Follow our Moxon vise plan and build your own portable Moxon twin-screw vise. The portable Moxon vise is designed to hold work above the standard height of a workbench. The Moxon vise design is widely attributed to a Joseph Moxon. Joseph Moxon (1627 – 1691), was the hydrographer to Charles II English printer specialising in mathematical books and maps. Moxon’s 17th century book The Art of Joinery first described the double-screw vise. In this historical publication the Moxon vise was documented – a double-screw held to a workbench top with clamps or holdfasts in order to facilitate certain work. Comprehensive information, Moxon vise techniques and video, large photos and (14) detailed computer designed diagrams (CAD) included with the Moxon vise plan purchase. Images, video and illustrations of attaching the Moxon vise to a workbench are also included.

Comprehensive information, Moxon vise techniques and video, large photos and (14) detailed computer designed diagrams (CAD) included with the Moxon vise plan purchase. Images, video and illustrations of attaching the Moxon vise to a workbench are also included. Mortising for the captive nut in the rear jaw inside face was performed using bevel-edge and mortise chisels. Hard maple is well.. hard! In this case, the mortise chisels excelled at hogging out material from the 3/4 inch deep mortise. With a softer hardwood, lighter bevel-edge chisels would have been sufficient. I also oriented the nut so it would align well with the long edges of the rear jaw, mostly an aesthetic consideration.

Mortising for the captive nut in the rear jaw inside face was performed using bevel-edge and mortise chisels. Hard maple is well.. hard! In this case, the mortise chisels excelled at hogging out material from the 3/4 inch deep mortise. With a softer hardwood, lighter bevel-edge chisels would have been sufficient. I also oriented the nut so it would align well with the long edges of the rear jaw, mostly an aesthetic consideration. After test-fitting the Benchcrafted hardware and ensuring it worked smoothly, the next step was to attach a large block of wood to the rear. This block of wood would both stabilize the vise assembly and allow holdfasts to be used to clamp the Moxon vise to the workbench top. Several other intermediate steps were performed, always careful to get alignments exactly correct. There is almost no room for error in making these vises since replacing either of the jaws is both time and material consuming. A more in-depth article on how I made this Moxon vise will be available at the web site soon.

After test-fitting the Benchcrafted hardware and ensuring it worked smoothly, the next step was to attach a large block of wood to the rear. This block of wood would both stabilize the vise assembly and allow holdfasts to be used to clamp the Moxon vise to the workbench top. Several other intermediate steps were performed, always careful to get alignments exactly correct. There is almost no room for error in making these vises since replacing either of the jaws is both time and material consuming. A more in-depth article on how I made this Moxon vise will be available at the web site soon. I’m not 100% sure of the origins of the Moxon vise design, but it is widely attributed to Joseph Moxon. Joseph Moxon (August 1627 – February 1691), hydrographer to Charles II English printer specialising in mathematical books and maps. Moxon’s 17th century book The Art of Joinery first described the double-screw vise. In this historical publication was documented the Moxon vise – a double-screw held to a workbench top with clamps or holdfasts in order to facilitate certain work.

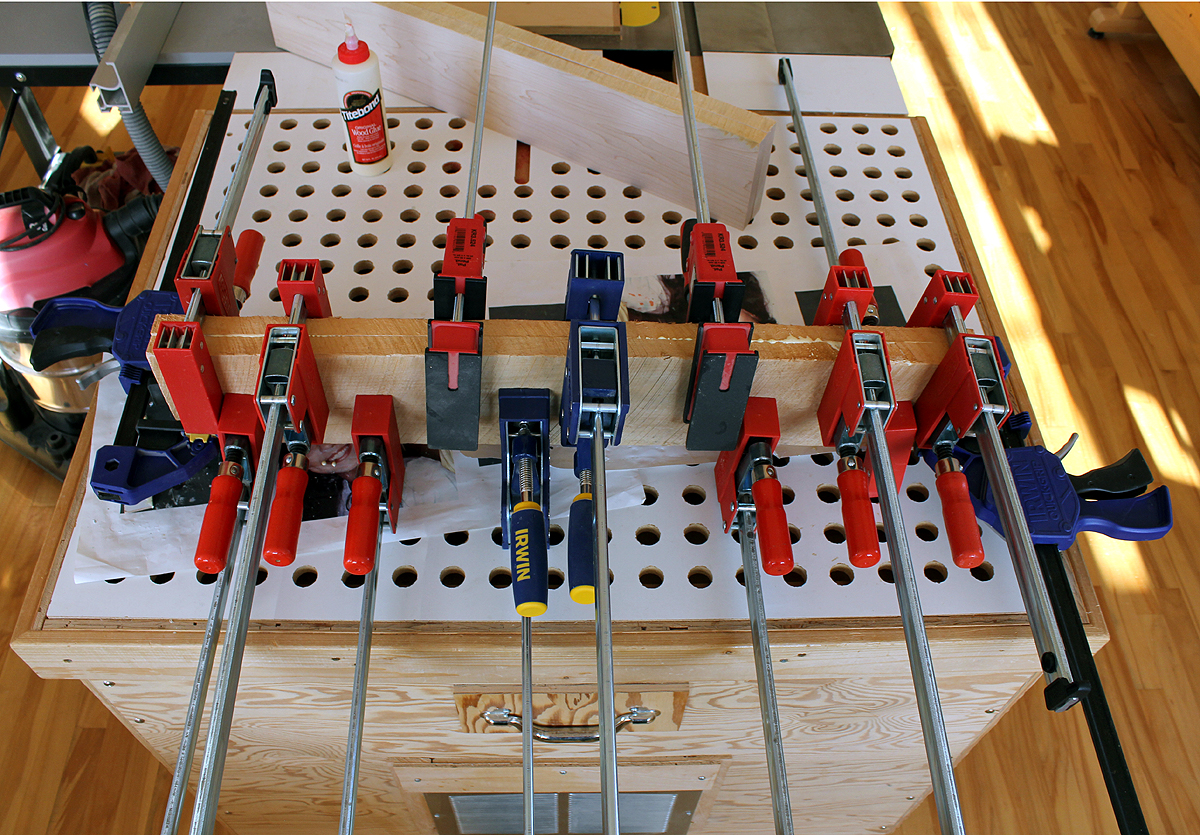

I’m not 100% sure of the origins of the Moxon vise design, but it is widely attributed to Joseph Moxon. Joseph Moxon (August 1627 – February 1691), hydrographer to Charles II English printer specialising in mathematical books and maps. Moxon’s 17th century book The Art of Joinery first described the double-screw vise. In this historical publication was documented the Moxon vise – a double-screw held to a workbench top with clamps or holdfasts in order to facilitate certain work. So after deliberating on the design, I simply went at it and worked on the front and rear jaws. Not having 8/4 stock available to me, I opted to laminate some 4/4 maple pieces instead. In the past, I have had success with the strength and stability of 4/4 boards laminated together. In selecting the boards, I mixed the grain orientations up so each of the laminated boards would counter the grain of the other board. This, in my opinion, balances out the internal stresses of the woods and keeps it all straight and stable. Laminating one of the jaws here with 4/4 boards. As they say, one never has enough clamps. In the pic above, this was almost the case, but it worked out. I do have other clamps, but for the most part, they are lighter.

So after deliberating on the design, I simply went at it and worked on the front and rear jaws. Not having 8/4 stock available to me, I opted to laminate some 4/4 maple pieces instead. In the past, I have had success with the strength and stability of 4/4 boards laminated together. In selecting the boards, I mixed the grain orientations up so each of the laminated boards would counter the grain of the other board. This, in my opinion, balances out the internal stresses of the woods and keeps it all straight and stable. Laminating one of the jaws here with 4/4 boards. As they say, one never has enough clamps. In the pic above, this was almost the case, but it worked out. I do have other clamps, but for the most part, they are lighter.